How Chitosan and PGPBs Can Support Early Development

Early-season performance sets the tone for crop production for the rest of the year. Seeds that germinate quickly, emerge uniformly, and develop strong root bases establish momentum that can be carried all the way through harvest. For crops that face unpredictable climates and biological or chemical pressures, it’s essential to lay a vigorous foundation for these early advantages.

Chitosan, the second most abundant biopolymer in the world after cellulose, has become one of the most useful tools for growers who want a more resilient kickstart to their crops. When precisely formulated and applied as part of the seed treatment program, chitosan demonstrates the ability to:

- Boost overall germination

- Accelerate speed to emergence

- Support stand establishment

- Fortifies plant defenses

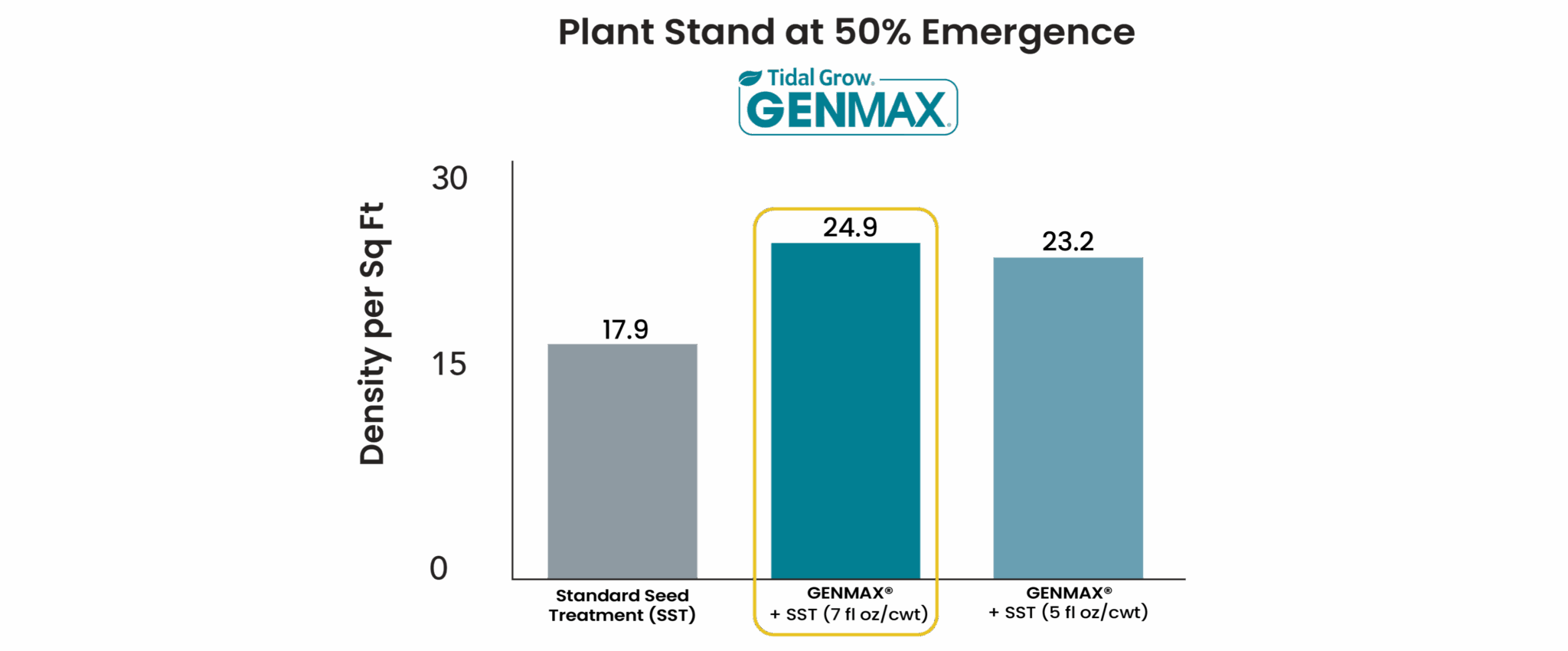

Whitewater, WI. The above graph demonstrates that adding .1 fl oz/CWT of GENMAX® to the standard seed treatment of Winter Wheat delivered the best results, increasing the plant stand emergence by 25% compared to the standard seed treatment.

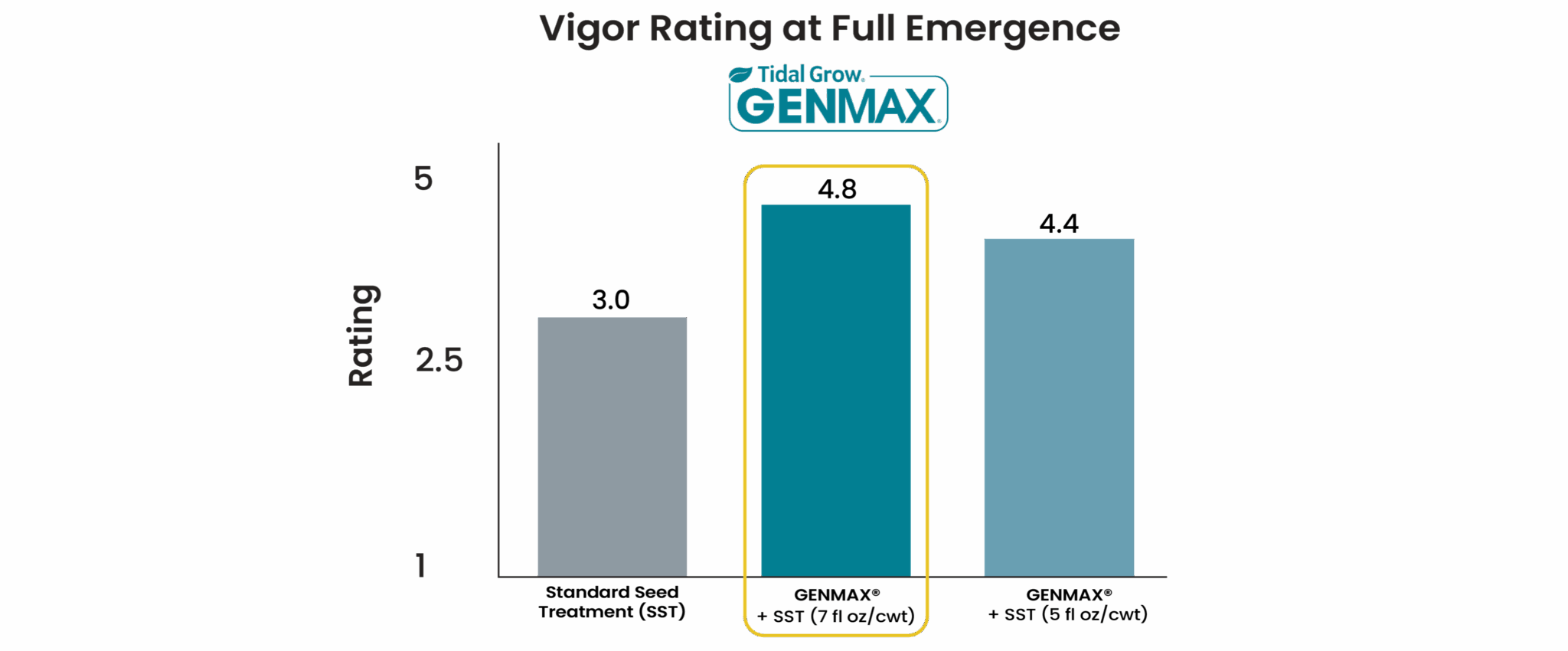

Whitewater, WI. The above graph demonstrates that adding .1 fl oz/CWT of GENMAX® to the standard seed treatment of Winter Wheat delivered the best results, increasing the vigor rating 5% compared to the standard seed treatment.

All these advantages support what growers are looking for today. However, the story of chitosan goes beyond its individual benefits. This blog explores how chitosan can become even more powerful when paired with plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB).

The Overlooked Partnership Between Chitosan and PGPBs

What’s often overlooked is the synergistic relationship between chitosan-treated seed and nearby PGPB. These beneficial microbes produce phytohormones that improve overall plant health and help defend against pathogens. Together, chitosan and PGPBs strengthen the plant’s stress responses, enhance nutrient uptake, and boost disease resistance. Their combined benefits are especially important in today’s production systems, where crops face a mix of biological, chemical, and environmental stressors that demand a resilient start from day one.

This synergy has become increasingly valuable in seed treatment plans where crops must endure multiple, overlapping stressors. A crop that can handle stress well from the outset is a crop with a more stable foundation as the growing season progresses.

PGPBs, including species such as Bacillus, Azospirillum, Rhizobium, Pseudomonas, and Streptomyces, are naturally occurring microbes found in the soil and around root systems. They support plant growth through nitrogen availability, nutrient mobilization, pathogen suppression, and hormone production.

Separately, both chitosan and PGPBs can strengthen a crop’s growth and resilience. But together, they amplify the benefits in multiple ways.

1. Both Act as Elicitors of Plant-Innate Immunity

Chitosan and PGPBs influence the production of key defense hormones such as:

- Salicylic acid (SA) – associated with pathogen defense

- Jasmonic acid (JA) – related to insect and stress responses

- Ethylene (ET) – involved in stress signaling and plant development

When both inputs activate these pathways, they reinforce each other’s effects, creating a more coordinated and efficient plant response.

2. Both Influence the Root Growth Powerhouse Auxin

Auxin are hormones that direct root growth patterns, such as:

- Root elongation

- Root formation

- Root hair development

- Overall below-ground system structure

PGPBs naturally produce auxins, which help the plant expand its root network. At the same time, chitosan influences auxin biosynthesis and transport, which increases plant sensitivity and responsiveness to key drivers of root growth. When the two work together, they jumpstart larger, more active, and better-equipped root systems.

3. Chitosan Enhances Root Exudates

Research has suggested that chitosan can modulate plant host responses through an immune response or root exudates, which can indirectly assist colonization and function of PGPBs. These exudates function as a communication bridge between the plant and microbes.

When chitosan stimulates exudation, it creates a more supportive environment for PGPBs to:

- Establish colonies

- Spread along root surfaces

- Access carbon sources

- Outcompete pathogens

The support that chitosan provides helps PGPBs work more effectively and earlier on in the plant’s development.

4. PGPBs Expand Root Development and Shield Plants

When PGPBs colonize roots, they can create a protective layer around the plant’s most vulnerable tissues. This presence creates several advantages to plants:

- Outcompeting pathogens for space—preventing infections

- Producing antimicrobial compounds

- Supporting nutrient uptake

- Improving stress responses

Chitosan supports the colonization of PGPBs by strengthening the plant’s immune system, while also giving microbes a more welcoming environment to live in. This results in a protective buffer where the plant and microbes reinforce each other’s strengths.

Literature Review: The Asparagus Study

The synergistic relationship between chitosan and PGPBs has been documented in multiple crops, climates, and seed management systems.

In one study on asparagus, the combination of chitosan and a PGPB, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, increased emergence rates, nitrate levels, root and shoot weights, and overall plant health. The results from this study are evidence that when chitosan is paired with microbes, it can help them function more effectively—especially in difficult growing conditions.

While the asparagus study is one specific example, similar benefits have also been observed in cereals, soybeans, and horticultural crops. The consistent performance across crop types highlights that the synergy between chitosan and PGPBs is crop-agnostic. Since fundamental biological processes are shared across species, such as plant hormones, microbial plant signaling, stress pathways, and immune activation, the combination of chitosan and PGPBs can perform across crops when applied properly.

Doubling Up Against Stress and Disease

Today, crops face increasing stress from multiple directions, temperature fluctuations, unpredictable moisture patterns, competition, pathogens, and soil health challenges. Chitosan and PGPBs team up to offer a strategy to help plants respond appropriately to their environment.

Chitosan’s Role in Stress Tolerance

Chitosan can stimulate the accumulation of osmolytes such as proline, a molecule that plays a key protective role in plant cells. Proline is a key player in safeguarding plant cells as it helps stabilize proteins, preserve membrane structures, and balance cellular water levels during stress. Because of this, chitosan-treated plants often demonstrate better resilience under salt stress, drought-like conditions, and environmental variability.

PGPBs Support Stress Resilience

PGPBs add an additional layer of protection by:

- Producing phytohormones that support plant growth during stress

- Occupying root surfaces so pathogens have fewer opportunities

- Releasing antimicrobial compounds

- Enhancing nutrient uptake when plants are under pressure

More active roots mean more water, more nutrients, and more consistency in less-than-ideal soils. When working together, chitosan and PGPBs double up as a defense system against stress and disease.

Chitosan Strengthens PGPB Populations

Some studies have shown that chitosan can increase the population of PGPBs in soil. This is likely due to its influence on root exudates and overall root development. The takeaway for growers is simple: stronger root systems give beneficial microbes more space to colonize and operate. When these microbial populations thrive, they support nutrient availability, boost root growth, and suppress harmful organisms.

All of this leads to a healthier, more resilient crop from the early growth stages, where plants are the most vulnerable, all the way to harvest.

Formulation Matters

Even though chitosan and PGPBs have a synergistic relationship, their relationship is still delicate. Not all chitosan formulations produce the same effects. Some formulations may even inhibit microbial activity. Critical formulation variables include molecular weight, degrees of deacetylation, etc. These factors will influence whether chitosan will support the activity of PGPBs, remain neutral, or become antagonistic.

Because the formulation determines how chitosan interacts with plant receptors, seed surfaces, microbe membranes, and signaling pathways, precision matters. Chitosan is not a one-size-fits-all input, and it is important for growers to choose the right formulation to unlock the synergy between chitosan and PGPBs, versus creating conflict between seed treatment and the microbial environment.

Why This Matters for Today’s Crop Production

Growers are being asked to do more with less: less predictable weather, less uniform soil, and sometimes less budget for seed treatment. Finding a seed treatment where growers can stack protections and advantages before the plant ever emerges is just one of the ways to ensure efficient and effective crops. Having a seed treatment that creates resilient crops prevents growers from having to apply other treatments later in the growing season, which also helps with small budgets.

Adding a precisely formulated chitosan seed treatment, like Tidal Grow® GENMAX® and Tidal Grow® GENBOOST®, delivers multiple benefits to relieve today’s growing challenges:

- Stronger germination and stand establishment

- More rapid and uniform emergence

- Healthier and more active roots

- Enhanced nutrient uptake pathways

- Stronger early immunity

- Synergistic microbial performance

- Better stress tolerance

Because chitosan works by enhancing natural plant processes, not by acting as a synthetic chemical, it fits seamlessly into production systems. Whether growers are looking to reduce synthetic inputs, layer in microbial seed treatments, or are simply striving for a more resilient early-season crop start, chitosan is the ideal tool to strengthen growth systems.

Want to dive deeper? Learn more in our blog posts. Read about Chitosan in Agriculture, explore The Power of Seed Treatments, or see Tidal Grow AgriScience’s Sustainable Path Forward.

Citations

Alhasawi, A., & Appanna, V. D. (2017). Enhanced extracellular chitinase production in Pseudomonas fluorescens: Biotechnological implications. AIMS Bioengineering, 4(3), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.3934/bioeng.2017.3.366 [aimspress.com]

Filipini, L. D., Pilatti, F. K., Meyer, E., Ventura, B. S., Lourenzi, C. R., & Lovato, P. E. (2021). Application of Azospirillum on seeds and leaves, associated with Rhizobium inoculation, increases growth and yield of common bean. Archives of Microbiology, 203, 1033–1038. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-020-02092-7 [link.springer.com]

Kovaleski, M., Maurer, T. R., Banfi, M., Remor, M., Restelatto, M., Rieder, R., Deuner, C. C., & Colla, L. M. (2025). Biocontrol of plant pathogens by actinomycetes: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 41, Article 243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-025-04422-7 [link.springer.com]

Ortega-García, J., Holguín-Peña, R. J., Preciado-Rangel, P., Guillén-Enríquez, R. R., Zapata-Sifuentes, G., Nava-Santos, J. M., & Rueda-Puente, E. O. (2021). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens as a halo-PGPB and chitosan effects in nutritional value and yield production of Asparagus officinalis L. under Sonora desert conditions. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 49(3), 12414–12414. https://doi.org/10.15835/nbha49312414

Priya, S. B., Agrawal, S. B., Solanki, V., Kumar, A., Dwivedi, B. S., Shah, A. K., Patel, K. K., & Jatav, S. S. (2024). Microbial diversity of Rhizobium and Azospirillum under different agroforestry land use systems. Asian Journal of Crop Research and Improvement, 24(12). https://journalacri.com/index.php/ACRI/article/view/1020 [journalacri.com]

Qiu, C., Bao, Y., Lü, D., Yan, M., Li, G., Liu, K., Wei, S., Wu, M., & Li, Z. (2025). The synergistic effects of humic acid, chitosan and Bacillus subtilis on tomato growth and against plant diseases. Frontiers in Microbiology, 16, Article 1574765. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1574765 [frontiersin.org]

van der Meij, A., Worsley, S. F., Hutchings, M. I., & van Wezel, G. P. (2017). Chemical ecology of antibiotic production by actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 41(3), 392–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fux005 [academic.oup.com]

Yarullina, L., Kalatskaja, J., Tsvetkov, V., Burkhanova, G., Yalouskaya, N., Rybinskaya, K., Zaikina, E., Cherepanova, E., Hileuskaya, K., & Nikalaichuk, V. (2024). The influence of chitosan derivatives in combination with Bacillus subtilis on systemic resistance in potato plants. Plants, 13(16), 2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13162210 [mdpi.com]

Zhang, B., Lan, W., Yan, P., & Xie, J. (2024). Antibacterial and inhibition effect of chitosan grafted gentisate acid derivatives against Pseudomonas fluorescens. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 273(Pt 2), 133225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133225 [europepmc.org]